The 14th Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, unquestionably made his mark on the political landscape of the nation. Modi is well-known for his charismatic leadership style and powerful oratory abilities, and as a result of his influence on political discourse and public perception, his goals and objectives are frequently interpreted in a variety of ways. While some perceive him as a forward-thinking leader committed to the growth of the country, others have voiced worries about his management style and the idea that he wants to be treated like a king. We explore this contentious element of Modi’s reputation and look at both sides of the debate.

There is no question that the foundations for just and effective administration have been deteriorating for a while due to the bureaucracy’s growing politicisation. The efforts made by the architects of our constitution to safeguard and shield the civil service from political meddling have for many years achieved a high degree of impartiality, with the possible exception of the emergency. What is more significant is that it fostered the mindset that any suspiciously close relationship between bureaucrats and politicians (for mutual personal advantage) was adulterous and illegal.

In opposition to this philosophy, the newly approved Delhi Services Act legitimises the Babu-Neta connection. It guarantees that the political agenda of the Union government is imposed on an elected chief minister while proclaiming the primacy of politics and administration (euphemistically referred to as the executive) over the court. This statute undermines the very federal system that all Indian services were designed to preserve. The legal authority of the chief secretary and the home secretary of Delhi to overrule the chief minister undermines his control over the civil service, which is guaranteed under List II of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. The submissive position of the bureaucracy, which is at the heart of political governance’s effectiveness, is uprooted as a result, exposing officers to a field littered with mines and pits. Senior administrators and chief ministers have occasionally disagreed, but according to authorities, one of the riders on a horse must always trail the other.

Those who are familiar with Narendra Modi, however, are not outraged by this open politicking of the government since he has never concealed his disdain for its fundamental tenets of experience, merit, and seniority. Modi is obsessed with steadfast personal commitment, which is a quality that both the law and decades of experience forbid. Public administration is an open structure, and it should not be changed into a closed private limited company. But Modi’s fundamental fears drive him to choose his clique, frequently over the objections of several other capable bureaucrats. He honours loyalty and makes sure that every officer who has served him well is rewarded, frequently beyond his wildest expectations. This tactic aims to undermine government officials’ impartiality, which explains why many of them are supporting Modi’s actions that fall within the lines of grey and black. These “collaborators” frequently ignore the reality that their fingerprints can later be found in the contentious handover of national assets like airports, port regions, power utilities, and coal blocks to cronies because they are betting on his unwavering reign. These will demonstrate how far employees went to win the boss over. It is good to remind them that, in the coal dispute, it was eventually officials—even honourable ones—who received prison sentences.

The second less-discussed aspect of Narendra Modi’s performance as chief minister or prime minister is his extreme anxiety while using the English language. This is odd since Modi had the advantage of knowing Hindi, a second language, whereas Chaudhary Charan Singh and H.D. Deve Gowda could cope pretty well with a sensible blend of languages. However, his discomfort with English is clear and accounts for his fixation with Gujarati and Hindi. Regardless of their place of origin, he is not ashamed of choosing a vastly disproportionate number of officers from Gujarat. He installs them in the most important posts, ranging from the PMO’s all-powerful principal secretary to the leaders of various organisations through which he spreads fear. They explain documents to him in Gujarati or Hindi, and he admits that he detests reading written material. Working in Gujarat turns into an unheard-of asset, and today even a private sector employee of a crony firm rules Delhi.

His two restrictions significantly limit his options, which also explains the third, which is why he despises parting with his henchmen. Because of how deeply ingrained in his mentality his mistrust of untested officials is, the current cabinet secretary and home secretary are employed indefinitely. In reality, he overcame a legislative restriction to hire a plain-looking but dependable former officer as his primary secretary, as the first statute he altered after taking office as prime minister. Sanjay Mishra’s tendency to hold on is validated by the continual extensions he receives in his role as director of the now-infamous Enforcement Directorate.

Faustian Babu-Neta deals are apparently becoming more common under Modi, even if they undermine the values and culture of the public service. Despite harsh criticism, most of which is unwarranted, the civil service nevertheless manages to recruit talent. For the less than a thousand top positions in the highest levels of the public service, several lakh young people still compete each year. It is admirable that a significant portion of the bureaucracy does not conspire to assist the plutocrats and oligarchs who are preferred by the dictatorship, as this new blood transfusion helps preserve the best stream conceivable. This is clear from the conscientious officials’ refusal to permit the widespread privatisation of national assets at throwaway prices or even to engage in dubious leases of public buildings. This sparked Modi’s long-ago hatred for the IAS.

Modi prefers to use terror, which has an impact on many officers. Of course, he is not the only person to employ this patronage-or-punishment option, but he has taken it to absurd lengths. How else is it possible to explain how the stock market regulator SEBI ignored the fact that problematic firms’ valuations increased by 5,000% in just three years? Officials from the finance ministry at the time cannot claim to have been oblivious to what was going on. Similarly, it would be difficult for officials in the coal and electricity ministries to claim innocence while creating regulations that would allow a monopolist to manage coal imports at prices that are 8–10 times higher than local prices and charge us more money. Similarly, the record write-offs that were made during Modi’s nine years, totaling an astounding Rs 12.51 lakh crore, were known to (and participated in by) bank executives and ministry officials. This enormous sum was “adjusted” by permanently eliminating the money deposited in banks under the pretext of “cleaning account books.” However, in fact, fraudsters and allies like Mehul Choksi and Nirav Modi had access to luxurious travel.

The wealthiest have undoubtedly grown enormously richer thanks to Modi’s administration. Ambani saw an astounding growth in his wealth, from $18 billion in 2014 to $90 billion today. In 2014, Adani flew Modi on his own jet from Ahmedabad to Delhi (sending a variety of signals), increasing his net fortune from $8 billion to an astounding $140 billion in just eight years. Then, the Hindenburg report pierced it, bringing it down to its current value of $64 billion, which is still quite high. One saw that babus, who were adept at controlling these and other ‘best friends, ultimately achieved extraordinary success in service and even politics.

Few understand how this regime helps the wealthy get richer because the system is so complicated. Here’s an illustration. Examining India’s contentious ‘neutral’ stance during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reveals that it actually benefited two Gujarat-based Indian corporations more than it did the Indian people. The public sector refineries struggled to make any money for over a year as the foreign affairs minister and his army of exceptionally biassed employees, who bully anyone for speaking the truth, publicly defended Modi’s choice to buy cheaper Russian petroleum by defying the West. Long-term contracts required them to purchase their goods at substantially higher costs.

Two independent refineries in Gujarat snatched up cheap Russian crude and then re-exported petro-products at incredible profits (with little responsibility to deliver oil to our pumps). In the year 2022-2023, when Ukraine was destroyed, India sold 98 million metric tonnes of petroleum products for $97 billion, as opposed to the $67 billion we received for the same amount in 21-2022. The government forbids ONGC and IOC from exporting and making money. The government’s story and the BJP’s propaganda failed to reveal that Modi’s friends really benefited financially from the Ukraine policy. Another ex-diplomat is in charge of the petroleum ministry, and he and his employees don’t even explain to the public why our gas prices haven’t decreased despite decreasing import costs.

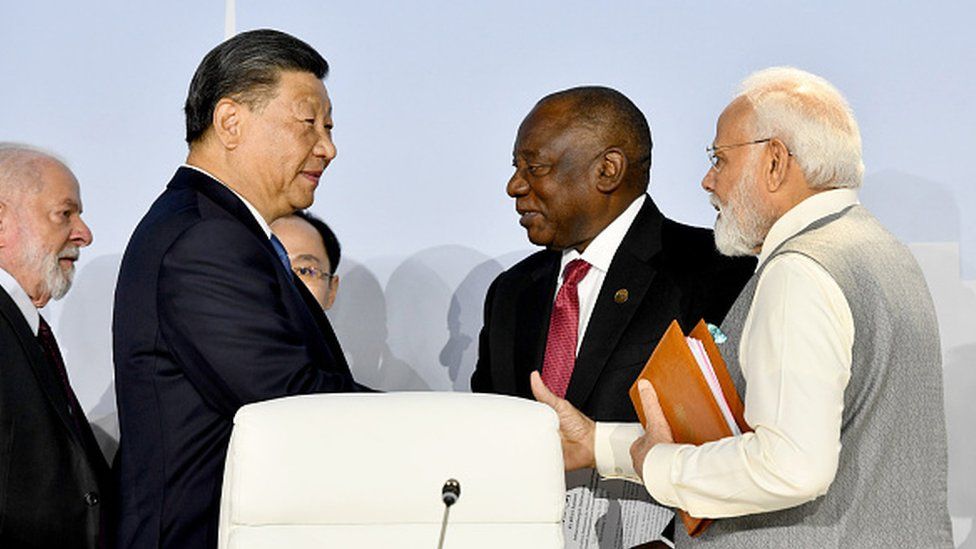

Every profession endures a few derogatory labels, but “courtier” is the best one for bureaucrats. Birbal, though, was one as well—a clever one. The calling is undoubtedly an important and valued one, despite the vilest detractors’ claims to the contrary. So much so that innumerable would-be candidates stay out with politicians far into the wee hours of the morning in an effort to gain entry into the ‘court’ of political leadership. However, as we have seen, the majority of ‘courtiers’ appointed by the Constitution still adhere to morals. The issue is that the current king does not recognise this and only rewards officials or courtiers who violate all decency in order to win his favour.

The subject of Narendra Modi’s leadership style is still up for debate, and there are many different points of view on it. He has had a significant effect on India’s political scene, regardless of whether one views him as a visionary committed to advancing the country or as someone looking for king-like treatment. It is crucial for people, academics, and policymakers to evaluate leadership styles critically in order to maintain the importance of democracy, transparency, and accountability as India develops and faces its complex difficulties.