Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s interview created more concerns than it answered regarding journalistic integrity, shattering India’s mainstream media landscape and exposing its weaknesses. Following the submission of his nomination, Modi made an astonishing statement in a televised interview with a media anchor who is more appropriately characterised as a mouthpiece than a journalist. In a show of emotion that Rahul Gandhi had foreshadowed weeks in advance, Modi denied ever calling Indian Muslims “infiltrators” or claiming that they were having more children. He was shocked and asked why discussions concerning big families seemed to focus only on Muslims. “Poor families in our nation also find themselves in this scenario. I made no mention of Muslims or Hindus,” he asserted vehemently.

“The day I do ‘Hindu-Muslim,’ I won’t be fit for public life,” Modi continued. A shrewd journalist could have pointed out, “He isn’t.” Many people who have followed Modi since his rise in the late 1990s, particularly after he served as Gujarat’s chief minister from 2002 to the present, agree with this sentiment.

Especially depressing was the response given by India’s English-language publications to Modi’s claims. Without questioning Modi’s validity, the Times of India and the Indian Express prominently displayed his remarks on their front pages. The headlines of the Times of India and Indian Express said, respectively, “If I do Hindu-Muslim, I won’t be fit for public life: PM Modi” and “The day I do Hindu-Muslim, I will be unworthy of public life.” I’m determined not to do that, PM Modi. Both newspapers repeated his remarks without question or context, failing in their basic journalistic obligation to confirm the facts and include background information

.

The fundamental problem stems from Modi’s Banswara speech, which was not nuanced or unclear. His comments were emphatic and captured on camera for everyone to see. Given this, Modi’s later denials called for careful investigation rather than mindless repetition. Ethical journalism would have placed his assertions in the context of his Banswara remarks, providing readers with the knowledge they needed to determine the truth. This is exactly what the India Cable newsletter did, telling its readers straight out about Modi’s lies.

Newspapers could have avoided publishing critical headlines and reporting even if, for a variety of reasons, they chose not to openly criticise Modi on their news pages. Editorial columns have the chance to refute Modi’s ludicrous assertions with simple reasoning that exposes their stupidity. If Modi was truly speaking of the “poor” and not “Muslims” when he made the comment about people “having more children,” he was suggesting that he would be against the Congress party’s commitment to help the underprivileged. This would imply that Modi was promising to thwart initiatives to reduce poverty, which is a ridiculous and unworkable stance. Major newspapers, however, chose not to investigate this stark discrepancy.

After a while, the Election Commission took notice and sent BJP President JP Nadda a direction over Modi’s address. Nadda’s defence of Modi’s remarks as “factual” in his reply simply served to exacerbate the uncertainty. This prompted a crucial query: what precisely was Nadda defending if Modi never stated what he is purported to have said? As The Wire eloquently noted, there is an inherent contradiction here: Nadha was endorsing statements that Modi claimed he had never made.

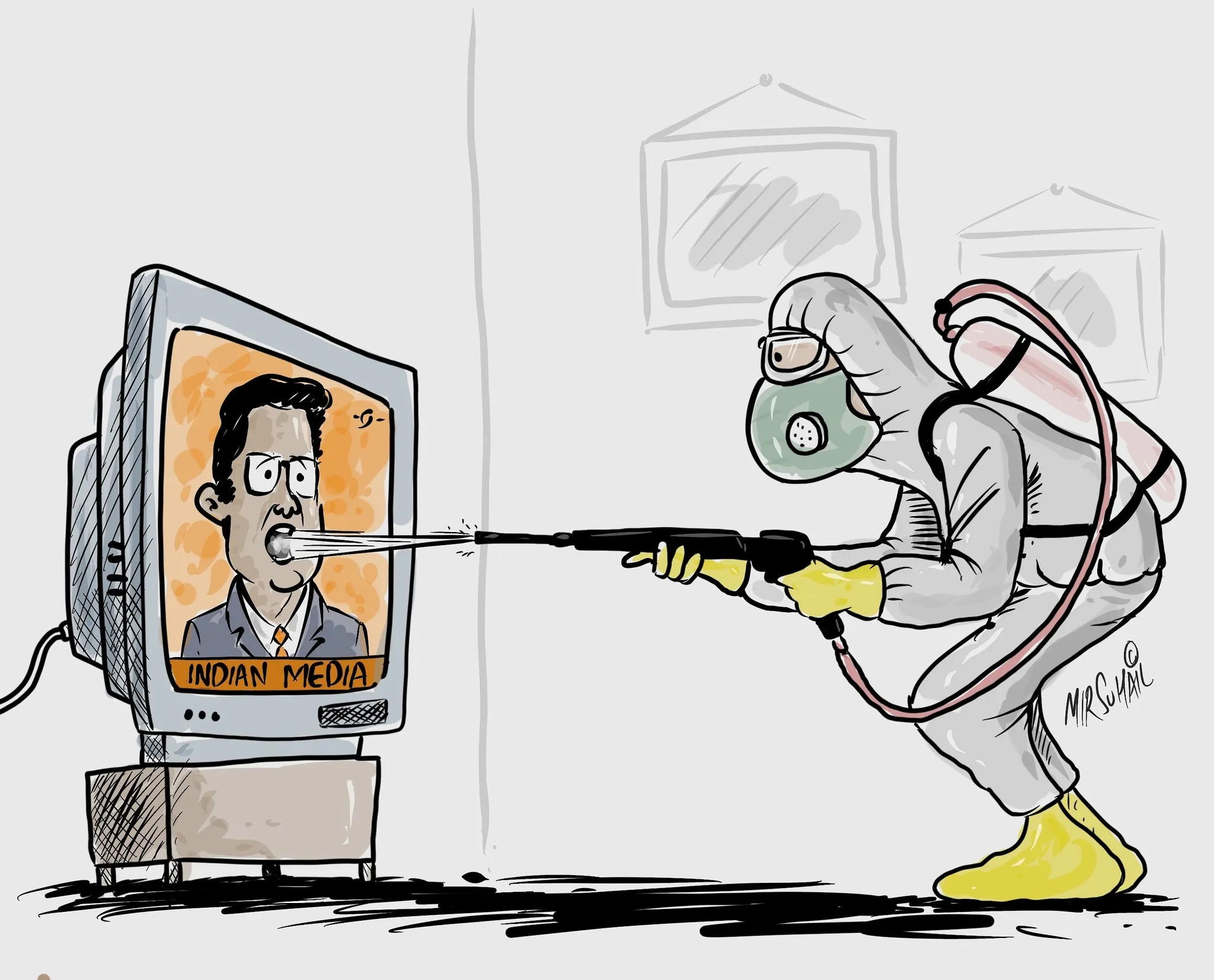

The entire incident highlights a very serious issue with Indian journalism. One counsellor to Modi’s ministry of information and broadcasting once derided the notion of speaking truth to power or holding the powerful accountable as the domain of activists, not journalists. Regrettably, the media tactics of today have a worrying resonance with this perspective. As a result, reporting has devolved into little more than the transcription of official remarks without any critical thinking or analysis—a practice known as stenographic journalism.

While Indian news television is in a sorry state, the problem has also affected print media, which used to have stronger standards. Major newspapers’ propensity to publish Modi’s claims without providing the necessary context is a sign of a wider deterioration in journalistic standards. Not only are individual reporters failing the public, but the media business as a whole is failing to question authority and give the public a thorough knowledge of political comments.

This decline has significant ramifications. The public should be informed, authorities should be examined, and democratic principles should be upheld via journalism. Media organisations threaten the foundation of democracy when they neglect these duties. Modi’s capacity to sway media narratives without facing strong opposition is indicative of a concerning decline in journalistic independence.

To sum up, the Modi interview incident and the media coverage that followed it provide a stark illustration of the problems facing Indian journalism. The media’s alarming tendency towards complacency and complicity is signalled by its failure to contextualise, question, and fact-check information. It serves as a wake-up call for the media to take back its position as an impartial observer, as opposed to a lapdog, and make sure that the facts always outweigh political spin. The most important responsibility of the media, as it teeters on the edge of collapse, is to speak truth to power in an unshakable and unflinching manner.