When compared to a year and a half ago, when its economy had just recently begun to recover from a destructive spike of the delta variety, India’s stock market remains unchanged in dollar terms. Despite this, its weight in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index has increased dramatically, surpassing Taiwan and South Korea to grab the second slot. Nearly all of the gain came at the expense of the index’s largest component, China.

Stocks in the second-largest economy in the world have dropped by two-fifths since June 2021 as a result of Beijing’s isolationist COVID-19 policies, turmoil in the real estate market, and a strong antitrust battle against the country’s valued tech giants. The overabundance of optimism in China is exactly the reverse of what is happening in India. Due to pent-up urban demand after the epidemic, stocks have held up relatively well despite the US Federal Reserve’s vigorous monetary tightening.

India’s MSCI Emerging Markets share has risen from 10% to 15% as a consequence, while China’s share has fallen from 35% in May 2021 to 28%. Will India’s outperformance come to an end as a result of the present openness of the Chinese economy? is the query that international investors will be asking in 2023.

If the experiences of other countries are any guide, China’s older people, of whom just 40% receive booster doses, would encounter chaos and probably catastrophic outcomes if the virus is allowed to spread across communities rather than being prevented. However, a quick reversal might boost vehicle sales, reawaken the sleeping real estate market, and raise consumer and corporate confidence from record-low levels. As a result, analysts could opt to increase their forecast of 4% profit growth over the next 12 months. Before the epidemic, these predictions were at 17%.

Both the drawbacks of COVID-19 and the advantages of reopening have passed for India. The economy is presently contracting despite the market’s ongoing froth. Despite some caution due to rising inflation (which hurts the margins of local consumer companies) and a global downturn, earnings are expected to rise by 18% over the next year (affecting software exporters). Bank optimism is at an all-time high. They benefit from expanding sales volumes and aggressive pricing; for instance, higher commodity prices have raised the demand for working capital loans while protecting interest margins.

The case for switching certain Indian stocks to Chinese ones is starting to look stronger. BNP Paribas has reduced its exposure to software exporters and removed consumer staples companies from its model portfolio, downgrading India from “overweight” to “neutral.” The market’s extremely high relative valuations and the potential for money reallocations to North Asia with China’s openness are what prompt Manishi Raychaudhuri, head of Asia research at BNP, to state that “our tactical caution on India derives from these factors.” Additionally, he notes that the volatility may rise as a result of the federal budget, which is the final one before the elections in 2024. India’s consumer-oriented equities are overrated, according to the general view.

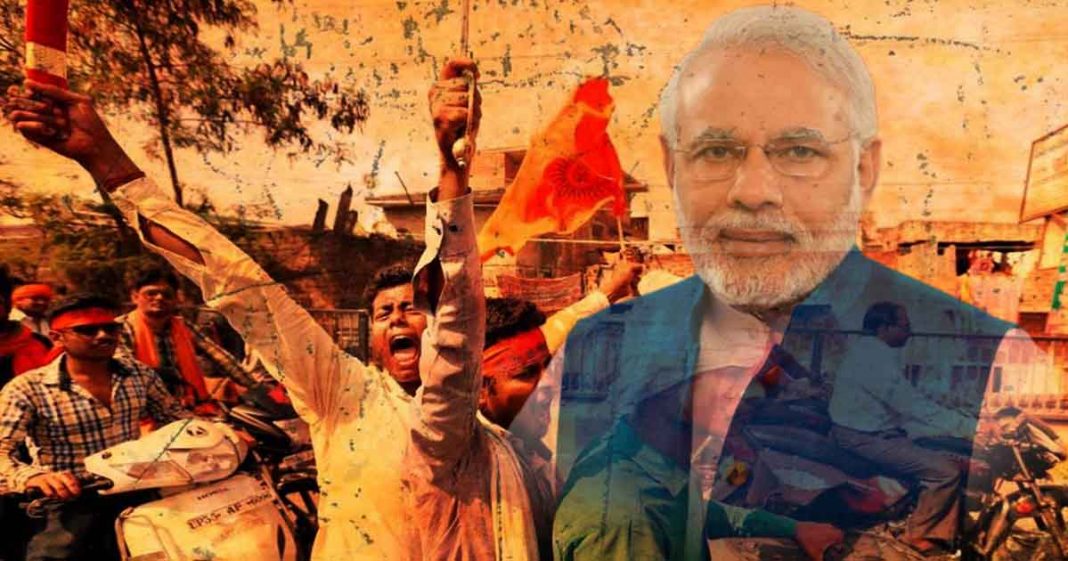

To increase its attraction to investors, India aspires to eventually be a competitive alternative to China. As President Xi Jinping’s actions widen the breach with the West, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is marketing his country as a location for international firms to minimise their overexposure to Chinese supply chains.

Although the manufacturers received $24 billion in subsidies, there is no guarantee that the risk will pay off. India faces three major obstacles in its quest to become “the next China,” according to Josh Felman, a former IMF official in New Delhi, and Arvind Subramanian, a former economic adviser to the Modi administration until 2018. These obstacles are: investment risks are too high; policy inwardness is too strong; and macroeconomic imbalances are too large.

Other countries have potential claims as well. Vietnam is on course to replace Britain in this year’s ranking of the seven countries with which the US trades the most products, as it is more open to trade than India. The Southeast Asian manufacturing giant didn’t enter the top 15 until 2019. Furthermore, even while New Delhi’s policies seem welcome on paper, it is far from clear that they will be applied equitably and won’t be changed to favour national champions, or “the huge Indian corporations that the government has backed,” according to Subramanian and Felman.

The BSE 500, a thorough index of the nation’s largest corporations, has increased by 33 per cent in local currency terms since 2021, with just the companies held by Gautam Adani, the richest businessman in India, accounting for one-third of the growth. The two richest tycoons own half of the gains when rival Mukesh Ambani’s telecom-to-petrochemicals conglomerate is taken into account.

Local investors, however, appear to have profited from a growing wealth concentration so far; they are neither excessively optimistic about the future of their country nor overly critical of its trajectory. This is because both countries’ prosperity is due to the same pro-capitalist policies. The combined pre-tax income of India’s biggest corporations, which was 7 trillion rupees ($85 billion) four years ago, was taken by the exchequer by over a third. There are already 13 trillion rupees in pre-tax earnings, but the government presently only receives around a fifth of that total. The importance of indirect taxes has increased, such as those on petroleum goods.

It’s not a favourable conclusion for India’s poor, who pay more in consumption taxes than the rich do, particularly in an atmosphere of inflation. The stock market is unlikely to raise concerns about the absence of major purchasing power outside of a small, rich class, though, given how little firms are taxed. India’s once wage-driven economy has evolved into a profit-driven one, and local investors seem to be fine with this. India’s managed investments, which include life insurance, mutual funds, retirement accounts, hedge funds, and portfolio services, have climbed from 41% to 57% of the nation’s GDP over the previous five years, according to Crisil, a division of SandP Global Inc. As the $1.16 trillion business penetrates more rural regions and smaller cities and towns, it may soon overtake the $2 trillion in bank fixed deposits.

China has seen a significantly more severe loss of foreign capital this year than India, with net outflows topping $187 billion. With its reopening, the People’s Republic of China will hire more people. It’s important to remember that a fast-expanding pool of local institutional liquidity is replacing the power of foreign fund managers, even if some of those funds are given at India’s expense. Foreigners won’t be able to overlook a nation where a significant local investment class has started to worship profit unless India Inc. provides decent earnings growth.