The intricate historical, political, and economic relationship between China and India has been characterised by these factors. Their dealings frequently show a delicate mix of collaboration and competitiveness since they are two of the Worlds most populous and powerful nations. China’s efforts to assert its influence over India have recently come into more focus, and this dynamic has important ramifications for the region and beyond.

There has been a long history of cultural and economic exchange between China and India, but there have also been territorial conflicts between the two countries, most notably along their shared border in the Himalayas. These tensions were made worse by the Sino-Indian War of 1962, which had a long-lasting effect on their diplomatic ties. The underlying tensions have persisted despite periods of thawing and strengthening relations.

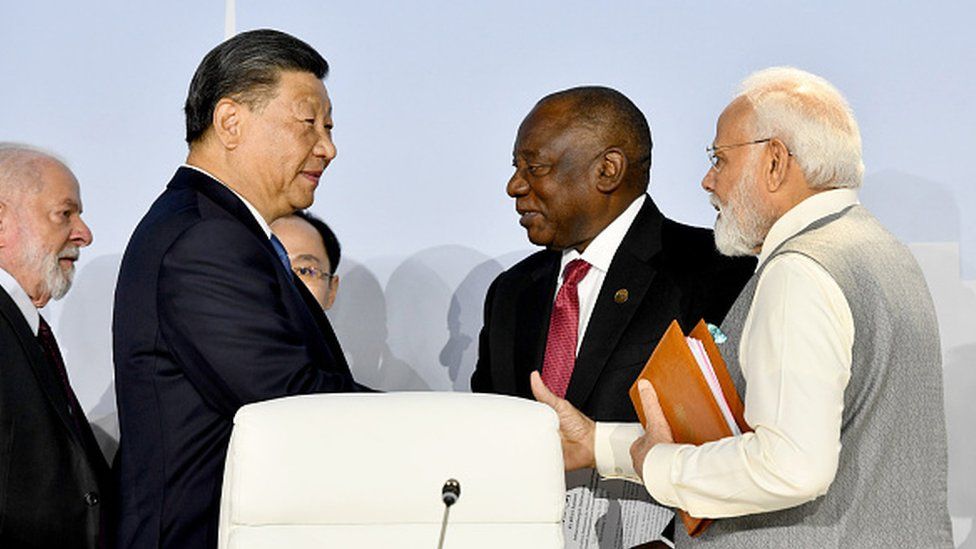

For many years, China saw India as a geopolitical outlier that sometimes needed to be disciplined with a military or diplomatic lesson to put it in its place. Between August 22 (BRICS) and September 9 (G20), Prime Minister Narendra Modi will cross paths twice with Chinese President Xi Jinping. As the conflict along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) festers, the talks between the two leaders will be quick, businesslike, and devoid of diplomatic niceties.

Due to China’s recent economic growth, which has made it a worldwide powerhouse, there is now economic competition between the two countries. Even though both nations have achieved significant economic progress, China’s rapid development has sometimes been considered a threat to India’s goals. China has increased its geopolitical power and reach via the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a vast infrastructural development project spanning Asia, Europe, and Africa.

On September 9, 2023, Xi will arrive in New Delhi for the G20 heads of government conference and be aware of a new world. An emerging power is India. The ascent of China has halted.

The stall is permanent. The three prosperous decades of China, when GDP growth frequently exceeded 10% annually, are finished. The weakening economy isn’t Xi’s main concern, though. An increasingly hostile West, led by the United States, confronts Beijing.

Six of the seven largest economies in the world will be pitted against Xi at the G20 meeting in New Delhi later this month: the US, Japan, Germany, India, Britain, and France.

Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia, won’t be present to support Xi. Others, such as Mohammad bin Salman of Saudi Arabia and Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, will diversify their holdings.

Xi’s attempts to leave China’s diplomatic mark on Middle Eastern affairs have had varying degrees of success. Beijing helped Saudi Arabia and Iran reach a détente and prodded the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) to accept Syria once more. To rekindle efforts towards a two-state solution to the Palestine issue, Xi visited Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian National Authority, in Beijing.

However, China is not yet enforcing its authority over the Middle East. Washington may be preoccupied with the conflict in Ukraine and its tumultuous domestic politics, but it still maintains military outposts there. Only one important military post has been established by China so far, and that is in Djibouti, which is located on the Horn of Africa.

In the meantime, China’s relations with Europe have gotten worse. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is about to lose Italy as its launching pad into Western Europe. Beijing’s grandiose plan to create a new Silk Route through Eurasia may come to an end due to China’s support of Russia in the conflict in Ukraine.

China continues to be the second-largest economy and a technical powerhouse in the world despite escalating issues both domestically and internationally. In automation, quantum computing, machine learning, and electric vehicles (EVs), it is the global leader. More passenger EVs are produced at Tesla’s gigafactory in Shanghai than at the company’s main facility in Austin, Texas.

But China is being excluded from the sector that counts today more than any other: chip manufacturing. The US, the Netherlands, and Taiwan are the three countries that dominate the world in the intricate ecology of chip manufacture and design.

Advanced chip technology transfer to China has been virtually prohibited by Washington’s Chips and Science Act, which was signed into law in August 2022. This implies that China will continue to lag behind the West in the most important cutting-edge sector of the global economy by one or perhaps two generations. Xi is aware of China’s ageing population. Its national debt is 282% of GDP, which is double the 130% of America. China had just come to the end of a five-year period of extraordinary growth when Xi became president in 2012. China’s GDP was $2.75 trillion in 2006. China’s GDP reached $7.55 trillion in 2011, virtually tripling in five consecutive years.

Meanwhile, India was experiencing political stagnation in 2011 under the control of the Congress-led UPA. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Congress got along well. An MoU was signed by the two sides in 2008, but its details are still secret.

August 7, 2008: “Shortly after party chief Sonia Gandhi and her family arrived in Beijing for the Olympics opening ceremony, the ruling Congress party in India and the Communist Party of China (CPC) on Thursday signed a pact to set up a mechanism that would help regular high-level exchanges between them. Additionally, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) gives the parties the chance to consult one another on significant bilateral, regional, and global issues.

Rahul Gandhi, the general secretary of the Congress, and Xi Jinping, the vice president of China and a member of the CPC politburo’s standing committee, signed the MoU in the presence of Sonia Gandhi, the party’s president, and Rahul Gandhi’s mother, sources informed IANS. Source: “It is strictly on a party-to-party basis.”

Before the MoU was signed, Sonia and Rahul Gandhi met with Xi and other top Communist Party of China officials to discuss topics of common interest, according to sources. One of China’s most well-known leaders, Xi, is largely seen as a leading candidate to succeed Obama as president in 2012.

“The fact that China decided to sign this document despite being aware of the recent developments in India shows it is attempting to forge ties with the Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi family in particular that go beyond the UPA government.”

A little more than a year after Xi entered office, the Narendra Modi-led NDA came to power in May 2014. At their informal encounter in Ahmedabad in September 2014, the Chinese president attempted to evaluate him firsthand. The two presidents were joined by Xi’s stunning singer-wife, Peng Liyuan, at the Sabarmati riverbank. There were then two further unofficial summits in Wuhan (2018) and Mahabalipuram (2019). They let each man gauge the other. Neither left feeling content. Xi realised that Modi was made of a different material than the Congressmen he had previously met.

In the meantime, Modi has established a tight strategic alliance with the West, led by the US. India needs to learn a lesson, Xi concluded. Early in Modi’s second term as prime minister, in April 2020, Chinese raids in eastern Ladakh started. By 2049—the centenary of the CCP’s founding—China aspires to be the world’s dominant superpower. But Xi is aware that, in order to accomplish that goal, China must first become an unbeatable regional force in Asia. India is the only nation with the size and scope, militarily and economically, to challenge China’s undisputed dominance in the parabolic arc that runs across East Asia, South Asia, and West Asia, from the South China Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.

Xi came to the conclusion that New Delhi needed to be put in its place by other means because Modi had refused to acknowledge India’s subordinate status to China through diplomacy at the summits in Ahmedabad, Wuhan, and Mahabalipuram. Galwan Valley was the next. Beijing’s Mandarins were unprepared for India’s following significant military build-up throughout the whole LAC; they were accustomed to India’s quiet supplicantry over Tibet and Taiwan.

The IMF estimates that India’s GDP by purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2022–2023 was $13,033 compared to China’s $33,014. As India’s GDP expands at a rate twice as fast as China’s GDP on average each year, the difference is currently 2.5 times smaller than it was five years ago.

How can China assert dominance over the US-led West if it is unable to do so militarily and economically over India? The US and India may form a G3 with the two angles of the triangle positioned against China, replacing the G2 architecture of global dominance between the US and China that Xi felt was inevitable.

Therefore, we should expect to witness a contemplative and reserved Xi in New Delhi on September 9–10 during the G20 heads of government conference, coming late and departing early. The Sino-Indian relationship is a complex web of tensions woven from the past, economic rivalry, and geopolitical ambitions. Even though China has demonstrated its superiority over India in a number of ways, it is crucial to examine this complicated dynamic from a nuanced angle. For the area to remain stable and for two of Asia’s most powerful countries to live in peace, it is essential to see the potential for cooperation as well as rivalry.