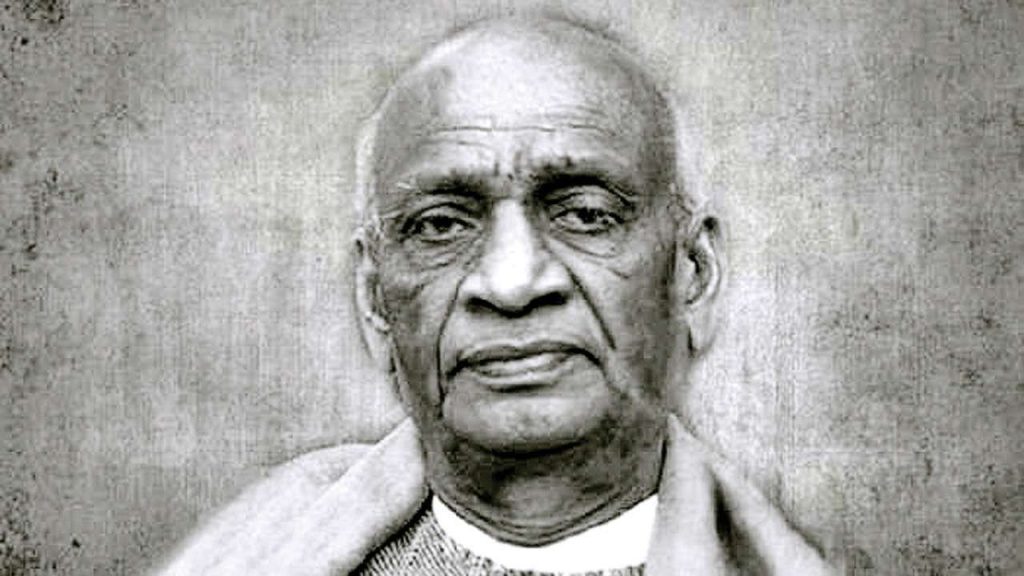

One of the most famous notes in Indian history is from 1949, written by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the country’s first home minister, about India’s policy towards China. An in-depth examination of the complex interactions between Patel and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru is necessary since they present a captivating story despite their periodic disagreements. Four crucial themes become apparent as we examine this historical artefact, providing insight into the intricacies of the post-colonial and post-war periods.

Sardar Patel’s intellectual fearlessness was one of his approach’s most notable features. Though Nehru was well-versed in international issues, Patel was not afraid to voice his opinions, contrasting the prime minister and securing them for future generations. Through this action, Patel not only demonstrated his bravery but also a leadership dynamic that allowed for the coexistence of different viewpoints.

Mahatma Gandhi also praised Patel for his capacity to keep an independent perspective. This willingness to disagree, along with an appreciation of Nehru’s wider perspective, identified a special aspect of their connection. In the area of international affairs, where Nehru had a greater influence, Patel’s readiness to express opposing opinions demonstrated a vibrant intellectual climate among post-colonial India’s leaders.

Asia saw a swift transformation during the 1940s and 1950s as countries struggled with independence. A new global order marked by the rise of new entities and leaderships was imposed upon China, India, and numerous other Asian nations. It is important to comprehend the uncertainties of this post-colonial, post-war era since states have experimented and, to borrow a well-known Chinese proverb, “crossed the river by touching the stones.”

It is difficult for younger generations to understand the intricacies of that age in today’s more settled world. Each country was treading unknown territory, and Patel and Nehru, among others, were instrumental in determining the course of their respective nations. In addition to being context-specific, the difficulties they encountered and the choices they made also reflected the general attitude of a time characterised by audacious experiments and cautious optimism.

An important context for the differences between Patel and Nehru’s viewpoints was India’s pervasive anti-colonial feeling. Both leaders were bound together by a common patriotism that was formed in the fire of the anti-colonial freedom movement, notwithstanding possible contrasts in their worldviews. Even though each of them used a different strategy, they were all united by the common goal of freeing India from colonial rule.

It was inevitable that leaders would view the world and interact with other political groups differently. But a strong point of agreement was the mutual dedication to creating a “New India.” This shared goal, which had its origins in the anti-colonial movement, developed into a guiding concept for the young country, affecting choices and moulding foreign policy.

Throughout the post-colonial era, the leaderships of China and India struggled to keep control over their recently constituted countries and territories. There was no limit to this shared insecurity on either side of the border. Nehru and Patel were equally determined to establish control over Jammu and Kashmir and the North-East Frontier Agency areas, while Mao Zedong aimed to gain control over Tibet.

A recurring theme that highlighted the vulnerability of post-colonial states was the fear of losing newly won lands. Despite their divergent ideologies, China and India both had to accept the “ground realities.” Securing authority over large and diverse regions presented significant problems, and the leadership needed to strike a careful balance between accommodating regional desires and consolidating power.

Gaining an appreciation of the worries and goals of the political leadership of that era requires an understanding of their thinking. Several newly independent countries emerged in the post-colonial era, each battling a distinct set of difficulties. Some, like Vietnam and Korea, gained independence only to find themselves instantly divided. Some, like India, saw changes to their borders prior to gaining formal status. The complexities of this process of nation-building necessitate a careful analysis of the choices made by the leadership and the historical setting in which they occurred.

It would be simplistic to take a superior stance now and judge the leaders of the past according to views that have been formed over time. The benefit of hindsight should not obscure the intricacy of the leadership’s roles in determining the fate of developing nations, as they made judgements in an environment full of uncertainty and difficulties.

Recalibrating China-India relations was made possible by the aftermath of the 1962 conflict and the effects of the Cold War. The leaders of both countries worked to keep their relationship stable in spite of their previous conflict. Nonetheless, the glaring disparity in economic success between 1990 and 2010 “destabilised” this equilibrium.

China is now in a class by itself thanks to its quick ascent to become the world’s largest trading power and the second-largest economy. By 2010, China started to see itself as a comparable global force to the US. On the other hand, India and other Asian and African countries were still seen as having emerging economies. Their relationship began to be defined by the economic asymmetry.

A recent insight about the changing bilateral relationship made by a Chinese commentator in the Global Times is worth noting. The analyst noted that the Narendra Modi administration appeared to be taking a more realistic stance regarding the status of China and India. The way that Prime Minister Modi has handled the border problem has been notable, especially in not letting it worsen the relationship.

The Modi government’s change in the conversation around the trade deficit is equally important. Instead of concentrating only on China’s trade imbalance reduction measures, India has begun highlighting its potential for exports. Zhang Jiadong, the head of Fudan University’s Centre for South Asian Studies, emphasised this shift in perspective, which points to a more realistic approach from India.

The essence of China’s perception of India’s position is captured by this shift in India’s strategy towards the trade imbalance. The focus is on India’s recognition of its economic potential and power differential. The conversation surrounding the trade deficit changed when the Modi administration acknowledged the disparity in magnitude between the two economies.

In the past, China’s trade policies and the alleged “unlevel” playing field were frequently criticised by India. The latest change, however, suggests that the economic imbalance is becoming more widely accepted as India admits its “limited” export potential and subpar performance. This shift in viewpoint, which is a small but important change, represents India’s changing perception of its place economically in the world.

The insight made by Zhang Jiadong emphasises how critical it is to acknowledge China and India’s relative power and potential. The idea that Prime Minister Modi has at last come to terms with this fact fits in with the larger story of how their bilateral relationship is changing.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel both felt that China and India should be treated equally on the international stage; Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai may not have felt the same way. But their different approaches—in terms of performance as well as perceptions—marked a nuanced grasp of the geopolitical environment. Later, Indian leaders also struggled with these issues, which sparked a discussion that will not end until India improves its economic standing.

It would be a disservice to their intellectual prowess and dedication to creating a fully independent India if they were to posture and take on a superior attitude towards previous leadership. Leaders of the 1940s and 1950s had enormous obstacles, and decisions were made in a very different environment than in the modern era. Understanding the political leadership of that age and the delicate balance they attempted to maintain in the face of shifting geopolitical landscapes is necessary in order to fully understand the contributions made by Patel and Nehru.

To sum up, the 1949 message from Sardar Patel provides a starting point for comprehending the complexities of India’s relationship with China during a critical juncture in its history. Patel’s intellectual independence combined with the larger backdrop of a fast-evolving Asia, anti-colonial feelings, and post-colonial anxieties provide a thorough understanding of the difficulties faced by the leaders of that age. The ensuing economic divides and changing strategies in the twenty-first century highlight the lasting impact of Patel and Nehru, offering important insights into the intricate dynamics that continue to influence India-China relations.